Cold and hot packs are common self-treatment options used by many of us trying to deal with pain and injuries. But do we really know when to use cold vs heat? What does cold or heat really do to decrease pain and help us heal?

Cold and hot packs are common self-treatment options used by many of us trying to deal with pain and injuries. But do we really know when to use cold vs heat? What does cold or heat really do to decrease pain and help us heal?

Mechanisms of Pain

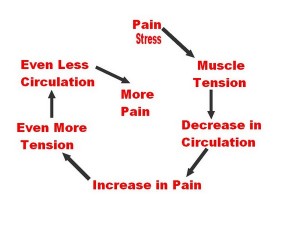

In response to tissue injury, specialized nerve endings called nociceptors are activated. Nociceptors transmit nerve signals that travel through the spinal cord to the brain, where the sensation of pain is recognized. At the same time, neurotransmitters initiate a spinal reflex that initiates muscle activity at the site of injury leading to a reflexive muscle contraction. If persistent, the increase in  muscle tone can cause painful muscle spasms, which can lead to further muscle damage due to decreased blood flow and oxygen to the surrounding tissues. Pain then increases. This injury process is called the pain-spasm-pain cycle. This cycle must be interrupted to prevent further tissue injury and to reduce the sensation of pain.

muscle tone can cause painful muscle spasms, which can lead to further muscle damage due to decreased blood flow and oxygen to the surrounding tissues. Pain then increases. This injury process is called the pain-spasm-pain cycle. This cycle must be interrupted to prevent further tissue injury and to reduce the sensation of pain.

Mechanisms to Decrease Pain

Temperature Receptors, called thermoreceptors, are specialized nerve endings that are activated by changes in skin temperature. Luckily, these receptors initiate nerve signals that block the pain signal processing that results from the pain-spasm-pain cycle.  Furthermore, heat or ice that is compressed into an injured area activates another type of specialized nerve ending called proprioceptors. Proprioceptors detect physical changes in tissue pressure and movement. Activation of proprioceptors block the transmission of pain signals to the brain similar to the addition of heat and ice creating a compounded effect.

Furthermore, heat or ice that is compressed into an injured area activates another type of specialized nerve ending called proprioceptors. Proprioceptors detect physical changes in tissue pressure and movement. Activation of proprioceptors block the transmission of pain signals to the brain similar to the addition of heat and ice creating a compounded effect.

Cold Therapy

Also known as cryotherapy, is the application of any substance to the body that removes heat from the body, resulting in decreased tissue temperature. Cryotherapy decreases tissue blood flow by causing vasoconstriction (narrowing of the blood vessels), and reduces tissue metabolism, oxygen use and inflammation. It is a cheap, effective, drugless method for temporarily relieving the pain of injuries. Safe application of ice to your skin can relieve symptoms from fresh injuries like ligament sprains, muscle strains, bruises, and tendon injuries — virtually any situation in which soft tissues are inflamed by trauma. Basically, any injury that feels red, hot, swollen and inflamed might benefit from cold therapy. Icing is primarily a pain-reliever — and not an actual treatment. That is, it doesn’t “fix” anything. It’s mostly intended to simply numb painfully inflamed or other hurting tissues. Although some things that we think of as “inflamed” aren’t actually inflamed (more on this later).

Ice is also often helpful with chronic overuse or tissue fatigue injuries like carpal tunnel syndrome, tennis elbow, rotator cuff tendinitis or shoulder bursitis, iliotibial band friction syndrome, patellofemoral pain syndrome, shin splints, and plantar fasciitis. There are others, of course, but these are the most common. Ice may also be useful for degenerative age-related arthritis, and sometimes the nasty inflammatory arthritides (rheumatoid, ankylosing spondylitis).

How to Ice

An excellent method of therapeutic icing is to apply ice directly to the skin, via an ice cup, with no layer of plastic or fabric between your skin and the ice. This direct ice treatment maximizes the contact of the cold to the soft tissues and uses the process of evaporation to most efficiently conduct heat away from the skin.

In comparison, gel packs and bean bags (or a bag of peas) are weak cryotherapies. They tend to warm up too quickly, and they sometimes cannot shape themselves to the contours of the injured body part. There are times when they are handy or easier, but for serious icing of acute injuries or a stubborn tendinitis, you really need an ice cup.

How to Make an Ice Cup

A Styrofoam or paper cup is the cheapest and most effective injury management tool an athlete or weekend warrior can own. Have them stored and ready in the freezer because you usually can’t predict when you will need one. In case you haven’t figured out the recipe yet:

- Get yourself some Styrofoam or paper cups

- Fill the cups with water

- Freeze the cups of water

- When you need to ice, cut off the top inch of the cup to expose the ice but leave the rest of the cup intake to act as an insulated handle

If you are a hardcore athlete and need to ice constantly, you should get a more permanent ice cup like the CRYOCUP™ (we sell these at Back to Function for $10). It is reusable and will ensure that you always have a handy and effective ice source ready for those acute soft tissue injuries. In a pinch, with no cups around, just use an ice cube held in a dishtowel — less convenient, especially for larger areas, but nearly as effective.

How to Use the Ice Cup

Massage the ice over the inflamed area in a slow but steady pattern. It’s important to keep the ice moving, as long as you don’t try to ice such a large area that tissue gets a chance to warm up before you return to the starting point. An ice treatment will feel like it is burning or stinging at first, and that’s okay. Icing this way can feel a bit nasty, especially at first in certain locations, but stick with it. In many situations, this is a much better solution than anti-inflammatory medication. Continue ice massaging for 1–3 minutes, or until it is numb, whichever comes first — no more. “When you’re numb, you’re done,” is the rule of thumb for safety. Areas with thick tissue, like the thigh, will take longer to get numb. Thin areas, like the wrist, will usually go numb quickly.

What does numb feel like? Just close your eyes and lightly touch the skin. If you can’t feel it at all, or if you can feel only pressure, that’s numb enough. Stop icing and let the tissue warm up. You may have heard that bare ice is too cold to use directly on the skin in this way. Although a cold-sensitive person may find direct ice too uncomfortable, tissue damage can only occur after sustained icing — well after you have gone completely numb, at least 3 minutes. Stopping roughly when you get numb pretty much guarantees that you won’t hurt yourself.

How Many Times Should I Ice a Day?

Once your tissues warm up again, you can repeat the treatment. In fact, you can apply the ice as often as you like, as long as your tissues have a chance to mostly warm up between treatments. In the case of injuries, icing is mostly just useful while the injury is still hot, red, swollen or painful — this phase may last for a few hours or several days. When these signs begin to fade, you may be certain that you would have been stuck with them for a lot longer if you had not been icing. There is no research to support a certain number of icings per day. I tell patients you can ice 10-15 times per day as long as you stop when you feel numb or get to 3 minutes each time and you let the tissues warm up between icings. Ice for 3-5 days for acute injuries. Frequent icing seems even more important for conditions such as tennis elbow, plantar fasciitis, iliotibial band friction syndrome, patellofemoral pain syndrome and shin splints.

Conditions That Are Not Appropriate For Cold Therapy

The most notable condition that does not do well with ice is back pain caused by muscle tightness (trigger points or knots). Back pain almost always involves muscular trigger points (knots), which are more likely to be aggravated by ice and helped by heat! For this reason, the majority of people with back pain prefer heat, and a few have negative reactions to ice. For similar reasons, neck pain usually should also not be iced. Although experiments have shown that both ice and heat are modestly helpful for low back and neck pain, there are good reasons to err on the side of heat. Ice should only be used on the back by patients who clearly prefer it (for whatever reason), or when there is definitely a fresh injury.

Other conditions that are contraindicated in cold therapy are advanced diabetes, circulation insufficiency, cold allergy and nerve damage. A special precaution is to avoid applying ice therapy directly over superficial nerves like at the medial elbow and lateral knee.

Note: There is some preliminary research from mostly animal studies that using ice on inflamed body tissues might halt the inflammatory cascade and lead to slower healing and eventual instability of the area. These findings will be covered in a future article and will certainly confuse the issue of when or even if ice should be used for therapy. Currently, most healthcare providers still recommend ice for the above mentioned conditions.

Heat Therapy

Also known as thermotherapy, is the application of any substance that adds heat to the body resulting in increased soft tissue temperature. Heat therapy increases blood flow which facilitates tissue healing by supplying protein, nutrients and oxygen at the site of injury.

What is Heat Therapy Used For?

Heat is for tight muscles, chronic pain, and stress — taking the edge off the pain of muscle spasms and trigger points, or conditions that are often dominated by them, like back and neck pain, for soothing the nervous system and the mind (stress can be a major factor in many chronic pain problems).

How to Use Heat

There are many ways to heat yourself. Local heating means specific heating: applying a hot water bottle, heating pad, heated gel pack or bean bag to a specific place on the body. A good heating pad that you can use at home is the Chattanooga Theratherm Moist Heat Pack (sold on Amazon.com). Systemic heating means raising the entire body temperature with a bath or jacuzzi, steam bath, or piping hot shower. Both approaches can be effective.

How Many Times Should I Heat Per Day?

Similar to icing, there isn’t really any research to support a specific recommendation for how often to use heat. The general rule is, if it feels good and seems to be decreasing your pain symptoms, then do it. We generally recommend not heating for more than 20 minutes at a time and then letting the tissue return to normal temperature before using heat again. Make sure to use common sense so that you don’t end up burning your skin!

Conditions That Are Not Appropriate For Heat Therapy

Never apply heat to a fresh injury! Remember, ice is for injuries. Any time tissue has been physically damaged, it will be inflamed for a few days, give or take, depending on the seriousness of the injury. If superficial tissue is sensitive to touch, if the skin is hot and red, if there is swelling, these are all signs that your injury is still fresh, and should not be heated. Heating is for muscle knots or trigger points and muscle spasm, but not for physically injured muscle — muscle strains, pulled muscles, torn muscles. Damaged muscle is usually inflamed, not in spasm, and trigger points are a minor factor in the aftermath of the injury.

Other conditions that are contraindicated for heat therapy include diabetes, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injuries and rheumatoid arthritis.

What About an Injured Muscle?

If you’re supposed to ice injuries, but not muscles, what do you with injured muscles (a muscle tear or muscle strain)? Ice for the first few days for a true muscle injury. A true muscle injury almost always involves severe, sudden pain. If the muscle is truly torn, then use ice to bring down the inflammation. Once the inflammation is under control, switch to heat.

What Have We Learned About Cold & Heat Therapy?

Ice is for acute injuries, and heat is for muscle spasms. Heat can make inflammation worse, and ice can make muscle spasms worse, so they have the potential to do some mild harm when mixed up. Both ice and heat are a cheap, drug-free way of helping an array of pain problems. Just make sure you understand your injury so that you can pick the right cold/heat therapy to get you back to function as quick as possible.

References:

Nadler et al., The Physiological Basis and Clinical Applications of Cryotherapy and Thermotherapy for the Pain Practitioner. Pain Physician. 2004.

Paul Ingraham, SaveYourself.ca

My daughter hurt her thumb while doing a “set” in volleyball. It has been 8 months and it is still sore. We had xrays done and it found not to be fractured or broken. It was okay for a few months but she recently started the volleyball season again and went to set the ball and reinjured it. Is this going to be a lifetime pain for her or is there something that can be done?

Rosie,

Your daughter’s thumb injury sounds like a soft tissue injury. There are 6 major ligaments that stabilize the thumb and sometimes you can overstretch 1 or more of these ligaments that will cause pain. If you’re in our area of Los Angeles/Torrance/Lomita I would be happy to evaluate her injury and give you a more detailed assessment and diagnosis.

Dr. Chad Moreau