Walking into a gym filled with barbells, free weights, and machines can be intimidating, especially for inexperienced weightlifters. However, the risk of injury from resistance training is relatively low when compared to team sports, running, and other forms of exercise. About 4 injuries occur for every 1,000 hours of weight training (Triplett, 2016). The low back, shoulders, and knees are some of the major body regions of concern. Risk factors for upper extremity injury include decreased glenohumeral range of motion, scapular diskinesis, and decreased shoulder strength. Risk factors for lower extremity injury include decreased balance, decreased neuromuscular control during jump landing, and decreased lower extremity muscle strength (Triplett, 2016). Previous injury is one of the most substantial risk factors for future injury in active individuals in both the upper and lower extremities.

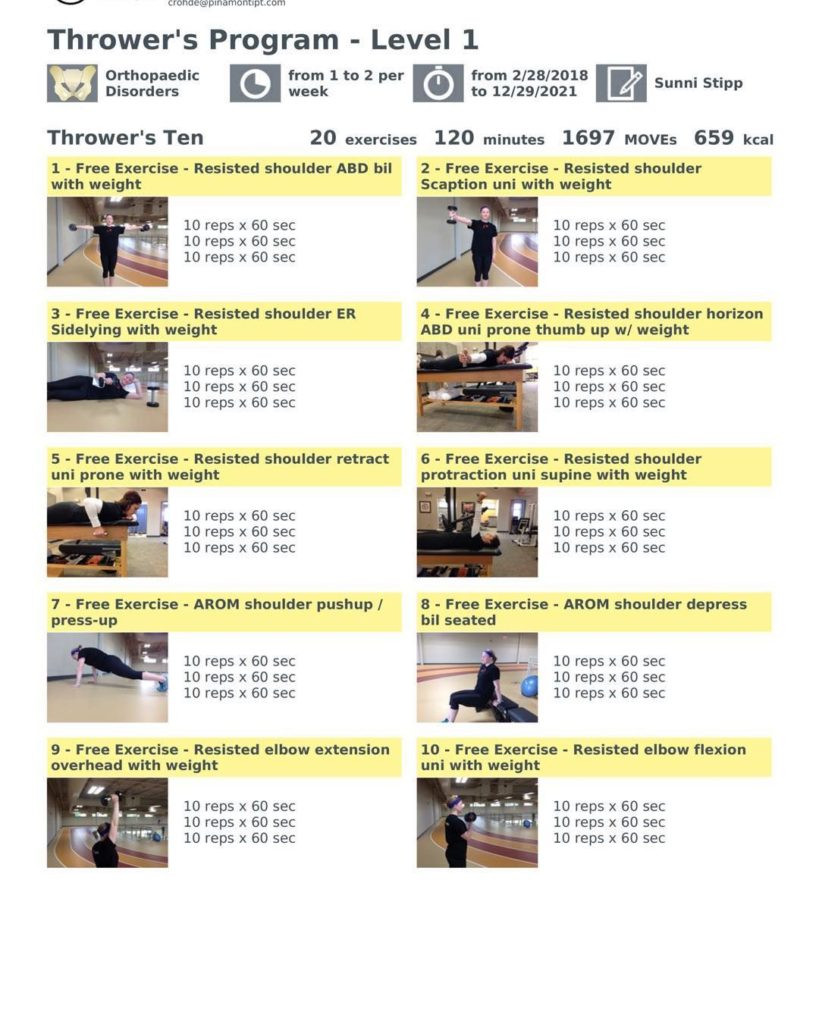

Risk management is the key to decreasing injuries in the weight room. When training loads are advanced too soon, there is an increased risk of injury and the potential for overtraining (Triplett, 2016). Lower extremity programs to reduce injury risk should be specific to the individual’s demands and should focus on the neuromuscular control required during specific activities such as landing from a jump or cutting when changing directions. Range of motion exercises and the Throwers Ten are often used to reduce upper extremity injury risk (Triplett, 2016).

Age is often a concern when it comes to resistance training. However, weight lifting can be a great exercise for older adults who want to increase strength, muscle tone, and bone density. Strenuous exercises have not been shown to cause any degenerative joint disease when progressively overloaded appropriately (Triplett, 2016). It is a common misconception that weight lifting is unsafe for children and adolescents. It is true that injuries to the growth cartilage may disrupt the bone’s blood and nutrient supply and result in permanent growth disturbances such as skeletal under or overgrowth, or malalignment of bone (Triplett, 2016). However, peak incidence of epiphyseal plate fractures occurs at the time of peak height velocity. This means that preadolescent children may be at less of a risk for epiphyseal plate fracture than an adolescent child experiencing a growth spurt. (Triplett, 2016). The risk of such damage can be reduced with proper exercise technique, sensible progression of training loads, and supervision by qualified strength and conditioning professionals. For more information regarding resistance training for youth, please see the position paper from the National Strength & Conditioning Association.

Lack of sleep is another risk factor for training-related injuries. Athletes should aim for 8-10 hours of total sleep per night (Bubbs, 2019). Experts have shown that getting less than 8 hours of sleep per night puts athletes at 1.7 times greater risk of injury than those who get at least 8 hours of sleep per night. This is due to reduced reaction time and cognitive function (Bubbs, 2019). Young athletes and young adults are especially at risk of accidents related to sleepiness and fatigue. A study of 496 adolescent athletes from 16 different sports found that the greatest overall risk for injury resulted when training load increased and sleep duration decreased simultaneously (Bubbs, 2019).

The best ways to reduce the risk of injuries in the weight room is to be supervised by a certified strength and conditioning specialist, obtain proper evaluation from qualified health care providers for current injuries, get at least 8 hours of sleep per night, and follow a training program that gradually progresses according to your capabilities and weight training experience.

Sources:

Haff, Greg, and N. Travis Triplett. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Human Kinetics, 2016.

Bubbs, Marc. Peak. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2019.